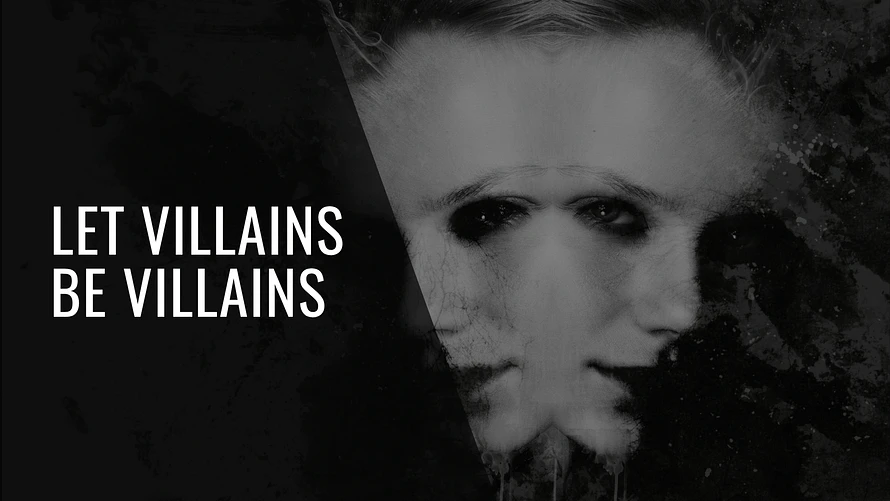

Let Villains Be Villains

Here’s a controversial take: sometimes a villain should just be evil.

- No tragic backstory

- No redemption arc

- No misunderstood childhood trauma to soften the blow.

Just pure, unrepentant malevolence—the kind that keeps you awake at night.

From Darth Vader’s suffocating breath to Maleficent’s cold, piercing smile, the most unforgettable villains have always captivated us not because we understood them, but because we didn’t. They weren't broken heroes or victims of circumstance—they were dark mirrors, reflecting our deepest fears with cruel precision.

But somewhere along the way, we decided that wasn't enough.

Modern storytelling, desperate to humanize everything, insists on peeling back the mask—explaining every shadow, every scar, every villainous choice until there's nothing left but sympathy.

Frankly, I couldn’t care less.

Sometimes, I don’t want to understand the monster. I don’t want to feel sorry for them. I want them to terrify me—to exist as raw, inexplicable threats that can't be reasoned with or redeemed.

Streaming platforms and cinematic universes have made villain origin stories increasingly common, each expansion chipping away at the primal fear these characters once commanded. What starts as an attempt to add psychological depth often ends up defanging them completely. When creators trade mystery for empathy, they don't just explain evil—they explain it away.

In this article, we’ll examine how several once-terrifying villains lost their edge when their shadows were dragged too far into the light—and ask the question no one seems brave enough to confront anymore:

Does understanding our monsters make them less monstrous?

Maleficent: From Menacing Witch to Misunderstood Fairy

In Disney's 1959 Sleeping Beauty, Maleficent wasn’t a character—she was terror incarnate.

She erupted in green flames at a royal christening, cursed an infant to death over a perceived slight, and transformed into a dragon wielding "all the powers of hell."

What made her unforgettable wasn’t just the horror she unleashed—it was what we didn't know about her. No motives. No wounds. No explanations. She simply was evil, and that terrible mystery made her magnetic.

Then came 2014’s Maleficent, where Hollywood’s compulsion to explain everything stripped away what made her terrifying.

Instead of an unknowable force of darkness, we got a betrayed fairy—a mutilated victim seeking justice. Angelina Jolie’s performance was captivating, but no amount of charisma could hide the damage: by understanding Maleficent’s pain, we were no longer afraid of her.

The visual shift told the story just as loudly: the regal menace of purple and black was replaced with soft natural beauty, elegance masquerading as power. Even her iconic dragon form, the raw physical embodiment of her fury, was handed off to another character, severing her from one of cinema’s most primal displays of villainy.

In other words:

-

In Sleeping Beauty (1959), Maleficent herself becomes the dragon — it's personal, it's monstrous, it's her rage made flesh.

-

In Maleficent (2014), she enchants Diaval into becoming a dragon to protect her — she doesn't transform herself at all.

This matters a lot thematically because:

➔ It distances her from owning her monstrous, terrifying power.

➔ It reduces her into a more passive, strategic figure rather than an unstoppable force of wrath and hellfire.

➔ It visually and emotionally defangs the primal horror of her character.

The original Maleficent endures because she embodied something primal and unknowable—the kind of evil that can't be rationalized, pitied, or forgiven.

Sometimes a villain’s power lies not in their tragedy—but in the terrible fact that there’s no explanation for their malice at all.

Loki: When the God of Mischief Lost His Bite

I love Loki. Truly. He’s one of my favorite antiheroes—sharp, venomous, beautiful in his cruelty. I adore how he antagonized Thor, how he danced on the edge of betrayal, chaos, and tragedy.

But few character arcs better illustrate the cost of villain domestication than Loki's fall from terrifying trickster to beloved, defanged antihero.

When Tom Hiddleston first brought the God of Mischief to life in Thor and The Avengers, Loki was a creature of genuine menace. His elegant exterior masked unfathomable rage. His silver tongue could spark genocide with a single lie and every glance, every grin, every whispered promise came with the threat of devastation.

He wasn’t a villain you rooted for—he was a god you feared.

The original Loki worked because he was unpredictable. Every gesture of brotherhood might conceal a knife; every smirk could precede carnage. His infamous "kneel before me" wasn’t just theatrical arrogance—it was a genuine threat from a god who no longer recognized the worth of mortals.

Having lost everything, he had nothing left to lose and that made him lethal.

But popularity became his undoing.

As audiences fell for Hiddleston's charisma, the character's jagged edges were sanded down. Sympathy replaced terror.

The Disney+ series Loki completed his domestication, transforming the would-be conqueror of Earth into a cosmic errand boy, wandering multiversal bureaucracy and wrestling with existential malaise.

What once was divine, untouchable fury was reduced to quips, jokes, and redemption arcs.

The god who once demanded the world kneel became a mascot for personal growth and in softening Loki to make him likable, they stripped him of what made him unforgettable.

And that, to me, is unforgivable—seeing a god who once shattered worlds now chasing purpose like a mortal desperate to matter.

Negan: The Walking Dead’s Ruthless Leader Turned Team Player

There aren’t enough words...or maybe there are just too many—to describe my unwavering hatred for this character.

When I said earlier that I don’t want to care about villains, don’t want to understand them, don’t want to like them—I was talking about Negan. The man who shattered MY beloved characters without hesitation. The man whose cruelty broke both the survivors—and me as a viewer—in ways that still ache.

I stopped watching Walking Dead because of Negan.

When Negan first stepped out of that RV, leather jacket gleaming, barbed-wire bat on his shoulder, The Walking Dead achieved something rare: they created a human monster more terrifying than the undead.

Jeffrey Dean Morgan’s performance turned what could have been a caricature into a force of nature—someone whose jovial charm made his brutality all the more chilling.

Here was a man who could smile while deciding which of your friends to murder.

Who could joke while destroying everything you loved.

Who made you realize that sometimes the worst monsters don’t rot—they breathe and what made early Negan truly frightening wasn’t just his capacity for violence—it was how inevitable that violence felt.

Every interaction was a performance designed to break his victims psychologically before he broke them physically. And he was so damn good at it, you believed no one was safe—not even the audience's hope.

But popularity and longevity demanded change. Through his imprisonment, his conversations with Father Gabriel, his mentorship of young Judith Grimes—Negan was softened. Humanized. Excused.

Each flashback, each redemption arc, stripped away another layer of terror. The unpredictability that made him a force of dread gave way to predictable heroics. The man who once proclaimed "I am everywhere" with chilling finality became just another weary survivor looking for redemption.

And that, more than anything, was a mercy he should never have been given. Negan's story arc should have ended in blood and his heart in Rick's hands.

Negan needed suffering, not salvation.

He needed to drown in his own cruelty—tied to a chair in a dark room, a "Let's play a game" whisper curling through the silence. Because some monsters are too dangerous to explain away.

And some villains should be broken, slowly and not redeemed.

The Grinch: When Hollywood Made a Monster Nice

Dr. Seuss's original Grinch was simple—and magnificent—in his malevolence:

"The Grinch hated Christmas! The whole Christmas season!"

That was all we needed to know.

No trauma.

No sob story.

No psychological profile cluttering the purity of his spite.

Boris Karloff’s chilling 1966 performance captured this perfectly, giving us a sophisticated villain whose hatred felt timeless, deliciously inexplicable, and gloriously unreasonable.

Even Jim Carrey’s manic 2000 portrayal, while adding backstory, preserved the Grinch’s essential cruelty. His version was still a bitter, twisted creature who reveled in ruining joy—a soul whose redemption felt earned because it was wrestled from real, seething malice.

But the 2018 Illumination version stripped away everything that made the Grinch compelling.

Benedict Cumberbatch’s Grinch wasn’t mean—he was just lonely.

Gone was the calculated cruelty.

Gone was the malicious pleasure in destruction.

Gone was the sophisticated, snarling spite that made his hatred something almost beautiful in its brutality.

Instead, we got a Grinch who needed a friend and a hug—less a monster, more a mopey outsider who just needed to be understood.

The problem wasn’t just the softening of his character, it was the fundamental betrayal of what made the Grinch endure.

The original Grinch’s power lay in mystery—we didn't need to know why he hated Christmas, because he wasn’t meant to be explained. He was the spirit of opposition itself—the dark, bitter corner of humanity that rebels against joy without needing a reason.

And that’s what made his redemption miraculous: it wasn’t inevitable. It wasn’t reasonable. It was a choice, ripped from the heart of something that never should have changed.

By turning hatred into sadness, and cruelty into loneliness, the 2018 film didn’t just soften the Grinch.

It didn’t humanize him. It hollowed him out.

Cruella De Vil: When Disney Declawed Their Most Fashionable Monster

In 1961’s 101 Dalmatians, Cruella wasn’t just evil—she was art.

A skeletal figure wreathed in cigarette smoke, with two-toned hair and a gleam of manic hunger in her eyes, Cruella was pure, fashionable malice.

She didn’t want power. She didn’t seek revenge. She didn’t crave love.

She wanted to skin puppies alive—because she thought it would make her look fabulous and she didn’t see a damn thing wrong with it.

Betty Lou Gerson’s iconic vocal performance made that monstrosity unforgettable: aristocratic disdain dripped from every word, turning materialism into something religious, even sacred.

"I live for furs, I worship furs"—not a justification, but a commandment.

Cruella was terrifying because there was no hidden wound to heal, no secret kindness buried deep inside. She was what she appeared to be: a monster wearing high fashion like a crown.

But then came 2021’s Cruella, where Disney decided this puppy-skinning sociopath needed... a sympathetic origin story.

- Gone was the gleeful wickedness.

- Gone was the pure, unapologetic malice.

Instead, we got Emma Stone’s scrappy, misunderstood fashion rebel—fighting against the industry, mourning her dead mother, sidestepping the very idea of harming dogs altogether.

The transformation was almost comical. The woman who once would have murdered dalmatians for a statement coat now... loves dogs.

The villain who once embodied haute couture cruelty was reduced to a quirky designer with mommy issues.

Stone’s performance was entertaining—but no performance could change the truth: the moment they tried to explain Cruella, they destroyed her. Defanging her wasn’t clever: t was cowardice.

Turning Cruella into a hero-in-waiting is like giving Hannibal Lecter a backstory where he’s a vegan activist fighting the meat industry.

You can do it, but in doing so, you lose everything that made the monster unforgettable.

Conclusion

I remember when villains used to be terrifying. When Maleficent didn’t need mutilated wings to curse an infant, when the Grinch’s heart could stay two sizes too small without a tragic backstory. When Cruella De Vil would skin puppies alive simply because she thought it would make a fabulous coat.

These were villains who kept us awake at night precisely because we couldn’t understand them and we didn’t need to.

But somewhere along the way, modern storytelling became allergic to unexplained evil.

- Every villain needed trauma

- Every monster needed motivation

- Every devil needed a redemption arc

I'm so over it, and I can't wait for Hollywood to stop, their desperate need to humanize the darkness. We traded genuine menace for relatable antiheroes, pure malice for sympathetic rebellion, mystery for melancholy.

We didn’t make villains more powerful.

We made them smaller.

Here’s a radical thought: Sometimes evil doesn’t need a reason and sometimes a villain should be cruel, inscrutable, and gloriously unknowable. Because in trying to explain away our monsters, we forgot why we feared them in the first place.

And after all—it's the shadows we can't explain that haunt us the longest.

XOXO

Athena Starr